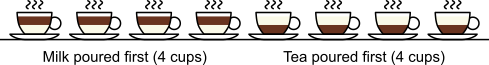

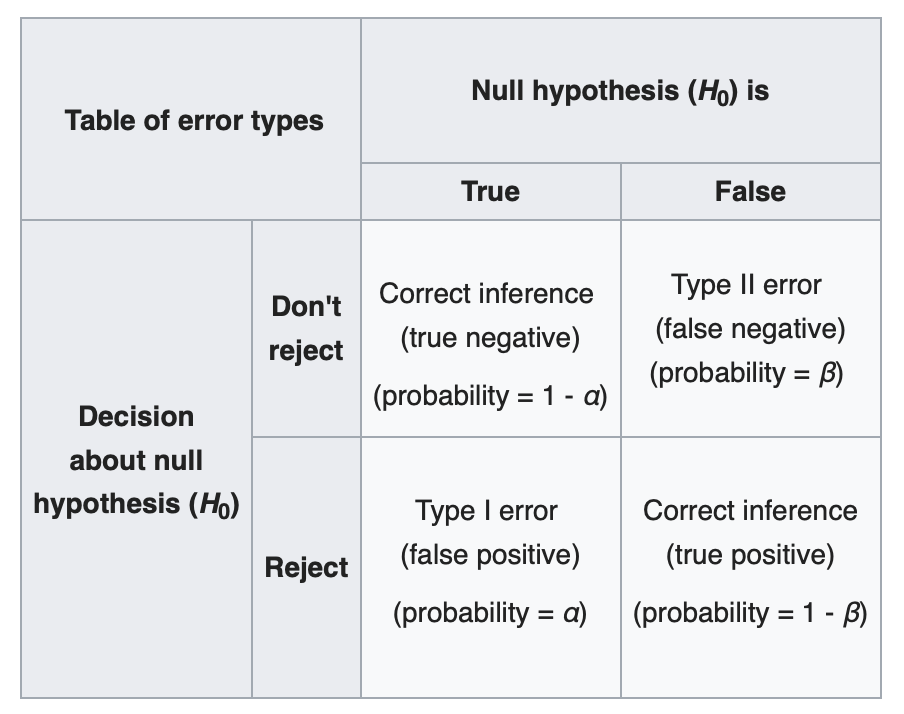

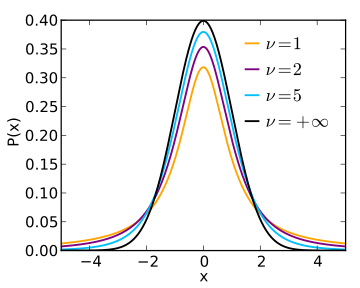

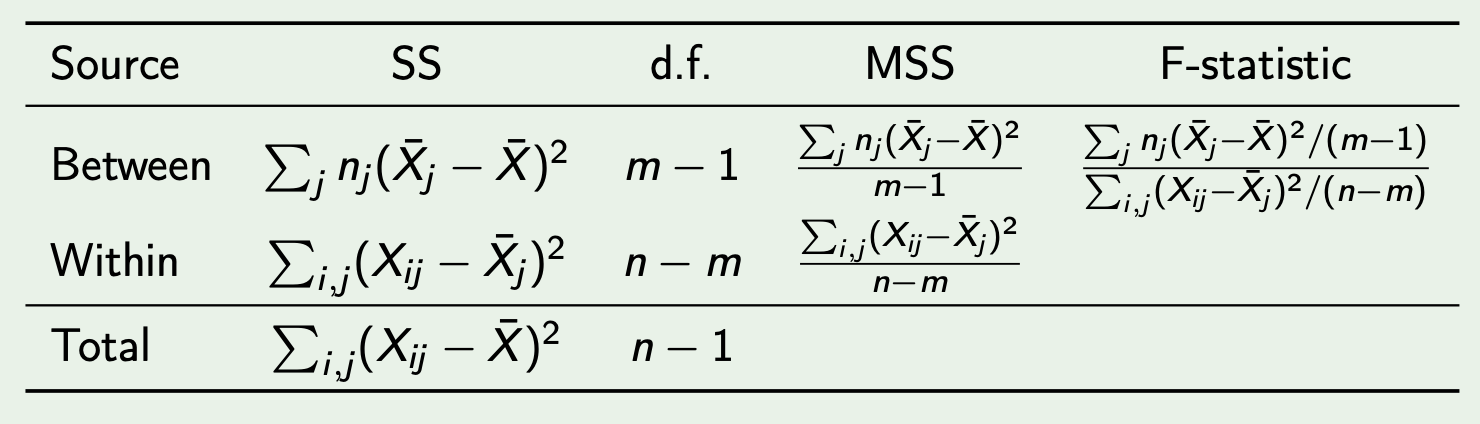

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # SR-5101 Advanced Research Skills ## (2/3) Hypothesis testing ### Dr. Haziq Jamil ### Semester 1, 2020/21 --- layout: true ### What's your proof? --- - _Imagine coming home and discovering this in your kitchen._ .center[] -- - Do you yell at Fido or do you not yell at Fido? That depends on whether he is innocent. How can I know? - Example adapted from Cassie Kozyrkov's blog post [here](https://medium.com/hackernoon/explaining-p-values-with-puppies-af63d68005d0). --- - Assume Fido is innocent (null hypothesis). How surprising would this evidence be if Fido is innocent? -- - Quantify it: What is the probability that (in this world where Fido is innocent) am I to see something at least as damning as the evidence we saw (in real life)? *This is the p-value*. -- - **Scenario A:** My four-year old is a cheeky little kid, maybe she put the lid on Fido. She does this quite often, so I have little reason to deny that Fido is innocent. *Not sufficient evidence to reject the null*. -- - **Scenario B:** My four-year old was at school. I guess my crazy neighbour climbed in through the window, ran all around the apartment, put the bin on the dog's head... but it doesn't seem very likely. *Reject the null*. -- - Note: We may never know what exactly happened, but we base decisions based on the likelihood of the evidence occurring. --- layout: true ### Lady tasting tea --- - Statistics provide the framework for discerning 'credible truth' by means of 'statistical significance'. -- - _Example: A lady declares that by tasting a cup of tea made with milk she can discriminate whether the milk or the tea infusion was first added to the cup._ -- - How do we know she's telling the truth? We can set up an experiment of course... -- - Eight cups of milk tea were prepared, four of which had the milk poured in first, and the remaining four had the tea poured in first. - The lady tastes the tea at random and tells us whether the tea or the milk was poured in first for each cup. - Note: She knows (because we told her) that there are four of each kind. So she only needs to tell us which four of the eight cups had the milk poured in first (or last). --- .center[] - The lady correctly guesses **1 out of 4**. Is she telling the truth? -- - The lady correctly guesses **2 out of 4**. Is she telling the truth? -- - The lady correctly guesses **3 out of 4**. Is she telling the truth? -- - How large is large? - We can use a hypothesis test to inform us the chance (p-value) of the lady correctly answering the taste tests, under the assumption that her claim is not true. - Low p-values indicate evidence supporting her claim (evidence against the claim is untrue). --- Well, assuming she has no ability to distinguish the cups of teas whatsoever, and that she is guessing at random, let's look at several probabilities. - There are `\({8 \choose 4} = 70\)` possible combinations of answers. - There is exactly one combination in which **all four answers are correct**. Therefore, the probability of guessing all correct would be `\(1/70 \approx 1.4\%\)`. This is also the probability of answering all incorrect. -- - If she correctly answers **3 out of 4**, there are `\({4 \choose 1} \times {4 \choose 3} = 16\)` cases of this happening, so the probability is `\(16/70 \approx 22.9\%\)`. This is also the probability of answering **1 out of 4** correct. -- - If she correctly answers **2 out of 4**, there are `\({4 \choose 2} \times {4 \choose 2} = 36\)` cases of this happening, so the probability is `\(36/70 \approx 51.4\%\)`. --- Suppose the lady answers `\(x\)` (out of 4) cups correct. The probability distribution table looks like this: | `\(x\)` | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |----------|---|---|---|---|---| | `\(P(X=x)\)` | `\(1.4\%\)` | `\(22.9\%\)` | `\(51.4\%\)` | `\(22.9\%\)` | `\(1.4\%\)` | -- What's the probability of observing a result equal to or better than `\(x\)`? | `\(x\)` | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |----------|---|---|---|---|---| | `\(P(X\geq x)\)` | `\(100\%\)` | `\(98.6\%\)` | `\(47.2\%\)` | `\(24.3\%\)` | `\(1.4\%\)` | These are the so-called `\(p\)`-values for this experiment! -- OK... but how do we make a decision? --- - The **significance level** is the measure of the strength of the evidence that must be provided in order to disprove the null hypothesis and conclude an effect is statistically significance. -- - The most commonly used significance level is `\(\alpha = 0.05\)`. - A `\(p\)`-value larger than the significance level `\(\alpha\)` indicates that there is not enough evidence in the data to reject the null hypothesis. - Note that: "Not reject" `\(\neq\)` "Accept" ! -- - On the other hand, observing a `\(p\)`-value smaller than the significance level `\(\alpha\)` is evidence for statistical significance. -- .center[.large[REMARK: WE ONLY HAVE THE POWER TO REJECT THE NULL HYPOTHESIS; A STATISTICAL TEST IS **INCAPABLE TO ACCEPT** A HYPOTHESIS.]] --- Back to the "tea-test" | `\(x\)` | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |----------|---|---|---|---|---| | `\(P(X\geq x)\)` | `\(100\%\)` | `\(98.6\%\)` | `\(47.2\%\)` | `\(24.3\%\)` | `\(1.4\%\)` | If we set a significance level of 5%, then it would seem that we can only reject the null hypothesis (which is that the lady is guessing randomly) **only if** she answers all four correctly. -- A value of `\(x=3\)` or `\(x=4\)` is observed with probability 0.243, which is quite substantial, given our "cutoff point" at `\(\alpha = 0.05\)`. --- layout: true # Fisher's exact test --- In 1935, Sir Ronald Fisher described the experiment involving the tea drinking lady in less than 10 pages in length. It is notable for its simplicity and completeness regarding terminology, calculations and design of the experiment. -- It gives rise to the **Fisher exact test**, a statistical significance test used in the analysis of contingency tables. For two dichotomous variables `\(X\)` and `\(Y\)`, we can distribute the frequencies as follows: | | `\(X=0\)` | `\(X=1\)` | Totals |--|:--:|:--:|:--:| | `\(Y=0\)` | `\(a\)` | `\(b\)` | `\(a + b\)` | `\(Y=1\)` | `\(c\)` | `\(d\)` | `\(c + d\)` | Totals | `\(a+c\)` | `\(b+d\)` | --- The setup is as follows: - Null hypothesis: The two variables are independent of each other. In other words, there is no difference in proportion between all cells in the contingency table. - Alternative hypothesis: There is some dependence between the two variables. - The probability `\(p\)` of observing such a value is .center[] - Need to also find probabilities for observing more extreme values than the one observed... these are then summed up to give the `\(p\)`-value. --- For the "tea-test", | | True milk first | True tea first | Totals |--|:--:|:--:|:--:| | Guess milk first | 3 | 1 | 4 | Guess tea first | 1 | 3 | 4 | Totals | 4 | 4 | -- The probability of observing this is $$ p = \frac{4!4!4!4!}{3!1!1!3!8!} = 0.229 $$ -- The more extreme case would be answering all correct with probability `\(1/70 \approx 1.4\%\)`. Summing these two probabilities give the same `\(p\)`-value as before `\(p = 0.243\)`. --- ```r TeaTasting <- matrix(c(3, 1, 1, 3), nrow = 2, dimnames = list(Guess = c("Milk", "Tea"), Truth = c("Milk", "Tea"))) TeaTasting ``` ``` ## Truth ## Guess Milk Tea ## Milk 3 1 ## Tea 1 3 ``` ```r fisher.test(TeaTasting, alternative = "greater") ``` ``` ## ## Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data ## ## data: TeaTasting ## p-value = 0.2429 ## alternative hypothesis: true odds ratio is greater than 1 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.3135693 Inf ## sample estimates: ## odds ratio ## 6.408309 ``` --- Other example applications of tests involving contingency tables: - Randomized experiment of drug trials: Some patients given Drug X and some Drug Y, observe how many cured and not cured. - [Gene set enrichment analyses](https://www.pathwaycommons.org/guide/primers/statistics/fishers_exact_test/): Is there any association between differentially expressed genes and annotations for any given Gene Ontology term? - Titanic example: Any difference in survival rates among passenger classes? ``` ## ## Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data ## ## data: titanic_survVSclass ## p-value < 2.2e-16 ## alternative hypothesis: two.sided ``` --- layout: true # `\(\chi^2\)`-test of independence --- Besides the Fisher test, this is a commonly used test for contingency tables. It tests whether or not the frequencies in a contingency table are evenly distributed. -- Let `\(X\in\{1,\dots,r\}\)` and `\(Y\in\{1,\dots,c\}\)` be two categorical variables. A random sample is obtained and their frequencies tabulated: | | `\(X=0\)` | `\(X=1\)` | `\(\cdots\)` | `\(X=r\)` | |:--------:|:--------:|:--------:|:--------:|:-----:| | `\(Y=0\)` | `\(O_{11}\)` | `\(O_{12}\)` | `\(\cdots\)` | `\(O_{1c}\)` | `\(Y=1\)` | `\(O_{21}\)` | `\(O_{22}\)` | `\(\cdots\)` | `\(O_{2c}\)` | `\(\vdots\)` | `\(\vdots\)` | `\(\vdots\)` | `\(\ddots\)` | `\(\vdots\)` | `\(Y=c\)` | `\(O_{r1}\)` | `\(O_{r2}\)` | `\(\cdots\)` | `\(O_{rc}\)` --- - An observation `\((X=i,Y=j)\)` occurs with (joint) probability `\(P(X=i,Y=j)\)`. The table simply tabulates the frequency with which `\((X=i,Y=j)\)` has occurred in the sample of `\(n\)` pairs of `\((X,Y)\)` observations. -- - If `\(X\)` and `\(Y\)` are independent, then `\(P(X=i,Y=j) = P(X=i)P(Y=j)\)`, and we expect cell frequencies to be `\begin{align*} E_{ij} = \frac{ \sum_{j=1}^c O_{ij} \times \sum_{i=1}^r O_{ij} }{n} \end{align*}` --- - Null hypothesis: `\(X\)` and `\(Y\)` are independent, i.e. the cell frequencies are row-wise and columnwise independent. -- - Under the null, we expect `\(O_{ij} \approx E_{ij}\)`. - The **goodness-of-fit** test statistic is defined as `\begin{align*} T = \sum_{i=1}^r\sum_{j=1}^c \left( \frac{O_{ij}-E_{ij}}{E_{ij}} \right)^2 \end{align*}` - The distribution of `\(T\)` is `\(T\sim\chi^2_{(r-1)(c-1)}\)`. - The `\(p\)`-value is calculated as `\(P\big(T>\chi^2_{(r-1)(c-1)}(\alpha)\big)\)`. --- For the "tea-test": ```r chisq.test(TeaTasting) ``` ``` ## Warning in chisq.test(TeaTasting): Chi-squared approximation may ## be incorrect ``` ``` ## ## Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity ## correction ## ## data: TeaTasting ## X-squared = 0.5, df = 1, p-value = 0.4795 ``` -- .center[*Gives incorrect results if cell counts are low (usually < 5 is considered low). Use Fisher exact test instead.*] --- For the titanic data set: ```r titanic_survVSclass ``` ``` ## ## 1 2 3 ## 0 80 97 372 ## 1 136 87 119 ``` ```r chisq.test(titanic_survVSclass) ``` ``` ## ## Pearson's Chi-squared test ## ## data: titanic_survVSclass ## X-squared = 102.89, df = 2, p-value < 2.2e-16 ``` .center[*When cell counts are large, it gives similar results to the Fisher test.*] --- Summary and comparison between tests for contingency tables - Fisher exact test - Use when cell counts (or expected cell counts) are small (less than 5). - Suitable for all sample sizes, but practically, large tables will require more computing power. - Criticised for being too conservative. - `\(\chi^2\)`-test - Use when cell counts are large (it is an asymptotic test). - More widely used in practice because of the criticism on Fisher exact test. (See [here](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fisher%27s_exact_test#Controversies)) --- layout: false # Type I and II error - A test is conservative if, when constructed for a given significance level, the **Type I error** is never greater than the significance level. *"Err on the side of caution".* .center[] --- layout: true # Goodness of fit tests --- The `\(\chi^2\)`-test can also be used to test whether an observed frequency of data matches a theoretically hypothesised distribution. -- *Example: A supermarket recorded the numbers of arrivals `\(X\)` over 100 one-minute intervals. The data were summarised as follows* | No. of arrivals | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | >3 | |-----------------|----|---|---|---|----| | Frequency | 13 | 29 | 32 | 20 | 6 | *Do the data match a Poisson distribution?* --- - The sample mean of arrivals is `\(\bar{X} = 1.77\)`. Under the null hypothesis, we assume `\(X\sim\text{Pois}(1.77)\)`. -- - We then expect the following frequencies to occur: $$ E_i = n \times P(X=i) = \frac{ne^{-\bar X}\bar X^i}{i!} $$ | No. of arrivals | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | >3 | |-----------------|----|---|---|---|----| | Expected | 16.4 | 29.6 | 26.8 | 16.2 | 11.0 | - Use the previous formula for the `\(\chi^2\)`-test. The degrees of freedom is "no. of cells - 1 - no. of estimated stuff". In this case it is 5-1-1 = 3. --- ```r sprmkt <- c(13, 29, 32, 20, 6) poisprob <- c(dpois(0:3, 1.81), 1 - sum(dpois(0:3, 1.81))) chisq.test(x = sprmkt, y = 100 * poisprob) ``` ``` ## Warning in chisq.test(x = sprmkt, y = 100 * poisprob): Chi- ## squared approximation may be incorrect ``` ``` ## ## Pearson's Chi-squared test ## ## data: sprmkt and 100 * poisprob ## X-squared = 20, df = 16, p-value = 0.2202 ``` ```r chisq.test(x = sprmkt, y = 100 * poisprob, simulate.p.value = TRUE, B = 10000) ``` ``` ## ## Pearson's Chi-squared test with simulated p-value (based ## on 10000 replicates) ## ## data: sprmkt and 100 * poisprob ## X-squared = 20, df = NA, p-value = 1 ``` --- Some notes - Without getting too technical, the `\(\chi^2\)`-test relies on normality of individual cells and also large sample sizes. Failing this, you may get a warning from R. - Solution is to simulate the `\(p\)`-values using Monte Carlo simulation. That is, simulate many, many tables from the null hypothesis, and count the proportions where the (simulated) test statistic is greater than the observed test statistic. - Use `simulate.p.value = TRUE` if get a warning. `B=10000` to control the number of simulations. - The above test may be used for continuous distributions (by discretizing). However, more appropriate methods exist (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test `ks.test`, Cramér-von Mises test `goftest::cvm.test`, etc.) for continuous distributions. --- layout:false class: inverse, middle, center # Tests for normal means --- ## Tests for normal means 1. `\(t\)`-tests - From one sample - From two samples (equal and unequal variances) 2. Paired `\(t\)`-test 3. `\(Z\)`-test a.k.a. Wald's test 4. ANOVA --- # `\(t\)`-distribution Looks similar to a normal distribution, but it has fatter tails. It is parameterised by its degrees of freedom. .center[] --- layout: true # One-sample `\(t\)`-test --- Suppose you collect a sample `\(\{X_1,\dots,X_n\}\)` which is assumed to come from `\(\text{N}(\mu,\sigma^2)\)`. Both `\(\mu\)` and `\(\sigma^2\)` are **unknown**. We are interested in testing, for a known value of `\(\mu_0\)`, `\begin{align*} H_0:& \mu = \mu_0 \\ H_1:& \mu \neq \mu_0 \end{align*}` We use the famous `\(t\)`-statistic `\begin{align*} T = \frac{\bar X - \mu_0}{\text{S.E.}(\bar X)} \end{align*}` and compare it against a `\(t_{n-1}\)` distribution. --- The two quantities in the formula are given by `\begin{gather*} \bar X= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n X_i \\ \text{S.E.}(\bar X) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar X)^2} \end{gather*}` -- We reject `\(H_0\)` at the `\(\alpha\)` significance level if `\(|T| > t_{n-1}(\alpha/2)\)`, or if the `\(p\)`-value given by `\(P(|T| > t_{n-1}(\alpha/2))\)` is less than `\(\alpha\)`. --- *Example: Student's sleep data—effect of two soporific drugs on 20 patients. Any increase in hours of sleep?* ```r head(sleep) ``` ``` ## extra group ID ## 1 0.7 1 1 ## 2 -1.6 1 2 ## 3 -0.2 1 3 ## 4 -1.2 1 4 ## 5 -0.1 1 5 ## 6 3.4 1 6 ``` ```r (x <- sleep[sleep$group == 2, ]$extra) ``` ``` ## [1] 1.9 0.8 1.1 0.1 -0.1 4.4 5.5 1.6 4.6 3.4 ``` --- *Example: Student's sleep data--effect of two soporific drugs on 20 patients. Any increase in hours of sleep?* "Is there an effect?" ```r t.test(x, mu = 0, conf.level = 0.95) ``` ``` ## ## One Sample t-test ## ## data: x ## t = 3.6799, df = 9, p-value = 0.005076 ## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.8976775 3.7623225 ## sample estimates: ## mean of x ## 2.33 ``` --- *Example: Student's sleep data--effect of two soporific drugs on 20 patients. Any increase in hours of sleep?* "Is there a positive effect?" ```r t.test(x, mu = 0, conf.level = 0.95, alternative = "greater") ``` ``` ## ## One Sample t-test ## ## data: x ## t = 3.6799, df = 9, p-value = 0.002538 ## alternative hypothesis: true mean is greater than 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 1.169334 Inf ## sample estimates: ## mean of x ## 2.33 ``` --- layout: true # Two-sample `\(t\)`-test --- Suppose now you collect two samples <u>independently</u> of each other: - `\(\{X_1,\dots,X_n\}\)` from `\(\text{N}(\mu_x,\sigma^2_x)\)` - `\(\{Y_1,\dots,Y_m\}\)` from `\(\text{N}(\mu_y,\sigma^2_y)\)` All means and variances are **unknown**. We are interested in testing `\begin{align*} H_0:& \mu_x - \mu_y = \delta \\ H_1:& \mu_x - \mu_y \neq \delta \end{align*}` -- In particular, for `\(\delta=0\)`, we are then interested in whether or not `\(\mu_x\)` and `\(\mu_y\)` are equivalent. --- There are two approaches: - Assume that the two variances `\(\sigma_x\)` and `\(\sigma_y\)` are **not equal**, so they come from two distinct distributions. - Assume that the two variances `\(\sigma_x\)` and `\(\sigma_y\)` **are** equal. This is called the "pooled variance" method. -- Note that the two samples need not be of the same size. We have `\(n\)` samples for `\(X_i\)` and `\(m\)` samples for `\(Y_i\)`. --- *Example: Student's sleep data--effect of two soporific drugs on 20 patients. Any difference in hours of sleep between two groups (treatment vs control)?* ```r (x <- sleep[sleep$group == 2, ]$extra) # treatment ``` ``` ## [1] 1.9 0.8 1.1 0.1 -0.1 4.4 5.5 1.6 4.6 3.4 ``` ```r (y <- sleep[sleep$group == 1, ]$extra) # control ``` ``` ## [1] 0.7 -1.6 -0.2 -1.2 -0.1 3.4 3.7 0.8 0.0 2.0 ``` --- *Example: Student's sleep data--effect of two soporific drugs on 20 patients. Any difference in hours of sleep between two groups (treatment vs control)?* "Is the mean of `x` the same as the mean of `y`?" Assume unequal variances. ```r t.test(x, y, var.equal = FALSE) ``` ``` ## ## Welch Two Sample t-test ## ## data: x and y ## t = 1.8608, df = 17.776, p-value = 0.07939 ## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## -0.2054832 3.3654832 ## sample estimates: ## mean of x mean of y ## 2.33 0.75 ``` --- *Example: Student's sleep data--effect of two soporific drugs on 20 patients. Any difference in hours of sleep between two groups (treatment vs control)?* "Is the mean of `x` the same as the mean of `y`?" Assume equal variances. ```r t.test(x, y, var.equal = TRUE) ``` ``` ## ## Two Sample t-test ## ## data: x and y ## t = 1.8608, df = 18, p-value = 0.07919 ## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## -0.203874 3.363874 ## sample estimates: ## mean of x mean of y ## 2.33 0.75 ``` --- layout: true # Paired-sample `\(t\)`-test --- Suppose now you collect two samples <u>independently</u> of each other: - `\(\{X_1,\dots,X_n\}\)` from `\(\text{N}(\mu_x,\sigma^2_x)\)` - `\(\{Y_1,\dots,Y_n\}\)` from `\(\text{N}(\mu_y,\sigma^2_y)\)` All means and variances are **unknown**. The difference here is that the data is **paired**, i.e. data are recorded pairwisely. Therefore the sample size of the two samples are equal. -- As usual, we are interested in testing `\begin{align*} H_0:& \mu_x - \mu_y = \delta \\ H_1:& \mu_x - \mu_y \neq \delta \end{align*}` --- In essence, we are interested in `\(Z_i = X_i - Y_i\)`, and this has distribution $$ Z_i = X_i - Y_i \sim \text{N}(\overbrace{\mu_x - \mu_y}^{\mu_z},\overbrace{\sigma^2_x + \sigma^2_y}^{\sigma_z^2}) $$ So this is treated similar to a one-sample `\(t\)`-test now. --- *Example: Student's sleep data*—If we inspect the data closely, the data actually come in pairs. <img src="lecture2_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-12-1.png" width="800px" /> --- *Example: Student's sleep data*—If we inspect the data closely, the data actually come in pairs. This is the code for the figure. ```r ggplot(sleep, aes(x = group, y = extra, col = ID, group = ID)) + geom_point() + geom_line() + scale_x_discrete(labels = c("Group 1", "Group 2")) + labs(x = NULL, y = "Increase in hours of sleep") + theme_bw() ``` --- *Example: Student's sleep data*—If we inspect the data closely, the data actually come in pairs. ```r t.test(x, y, paired = TRUE) ``` ``` ## ## Paired t-test ## ## data: x and y ## t = 4.0621, df = 9, p-value = 0.002833 ## alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.7001142 2.4598858 ## sample estimates: ## mean of the differences ## 1.58 ``` --- layout: true # Tests for proportions --- Suppose you have binary data `\(X_i \in \{0,1\}\)` for `\(i=1,\dots,n\)`. The distribution for `\(X_i\)` is Bernoulli with probability of success `\(p\)`. -- We would estimate `\(p\)` by the sample mean `\(\hat p = \bar X_n = n^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i\)`. -- We are now interested in testing `\begin{align*} H_0:& p = p_0 \\ H_1:& p \neq p_0 \end{align*}` -- For this test, we rely on the central limit theorem, which states that $$ \hat p \approx \text{N}\big(p_0, \hat p(1- \hat p)/n \big) $$ under the null, so we compare it against the top `\(\alpha/2\)` point of a normal distribution. --- *Example: Titanic data set* ```r head(x <- titanic$Survived) ``` ``` ## [1] 0 1 1 1 0 0 ``` ```r prop.test(sum(x), length(x), p = 0.5, conf.level = 0.95) ``` ``` ## ## 1-sample proportions test with continuity correction ## ## data: sum(x) out of length(x), null probability 0.5 ## X-squared = 47.627, df = 1, p-value = 5.154e-12 ## alternative hypothesis: true p is not equal to 0.5 ## 95 percent confidence interval: ## 0.3519194 0.4167722 ## sample estimates: ## p ## 0.3838384 ``` --- *Example: Titanic data set for different classes* ```r (nx <- table(titanic$Pclass)) ``` ``` ## ## 1 2 3 ## 216 184 491 ``` ```r (x <- table(titanic$Survived, titanic$Pclass)) ``` ``` ## ## 1 2 3 ## 0 80 97 372 ## 1 136 87 119 ``` --- *Example: Titanic data set for different classes* ```r prop.test(x[2, ], nx) ``` ``` ## ## 3-sample test for equality of proportions without ## continuity correction ## ## data: x[2, ] out of nx ## X-squared = 102.89, df = 2, p-value < 2.2e-16 ## alternative hypothesis: two.sided ## sample estimates: ## prop 1 prop 2 prop 3 ## 0.6296296 0.4728261 0.2423625 ``` Remark: this is identical to a `\(\chi^2\)`-test! --- *Example: Titanic data set for different classes* ```r chisq.test(x) ``` ``` ## ## Pearson's Chi-squared test ## ## data: x ## X-squared = 102.89, df = 2, p-value < 2.2e-16 ``` --- layout:true # One-way ANOVA --- Suppose you have data `\(\{X_{ij}\}\)` assumed to come from `\(\text{N}(\mu_j,\sigma^2_j)\)`. In each group `\(j\in\{1,\dots,m\}\)`, there are `\(i=1,\dots,n_j\)` samples. In total, `\(n=n_1+\dots+n_m\)` samples. Data looks something like this: | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | |:--------:|:--------:|:--------:|:--------:| | `\(X_{11}\)` | `\(X_{12}\)` | `\(X_{13}\)` | `\(X_{14}\)` | | `\(X_{21}\)` | `\(X_{22}\)` | `\(X_{23}\)` | `\(X_{24}\)` | | `\(X_{31}\)` | `\(X_{32}\)` | `\(X_{33}\)` | | `\(X_{41}\)` | `\(X_{42}\)` | `\(X_{43}\)` | | `\(X_{51}\)` | | `\(X_{53}\)` | | `\(X_{61}\)` | Question: Are the group means identical? --- The hypothesis we are interested in testing is `\begin{align*} H_0:& \mu_1 = \mu_2 = \cdots = \mu_m \\ H_1:& \text{ population means are not equal} \end{align*}` -- In most textbooks, you will find this ANOVA table: .center[] The test statistic follows an `\(F\)` distribution with `\(m-1\)`, `\(n-m\)` degrees of freedom. --- *Example: Classical N, P, K factorial experiment on the growth of peas conducted on 6 blocks with 4 measurements each.* ```r head(npk, n = 15) ``` ``` ## block N P K yield ## 1 1 0 1 1 49.5 ## 2 1 1 1 0 62.8 ## 3 1 0 0 0 46.8 ## 4 1 1 0 1 57.0 ## 5 2 1 0 0 59.8 ## 6 2 1 1 1 58.5 ## 7 2 0 0 1 55.5 ## 8 2 0 1 0 56.0 ## 9 3 0 1 0 62.8 ## 10 3 1 1 1 55.8 ## 11 3 1 0 0 69.5 ## 12 3 0 0 1 55.0 ## 13 4 1 0 0 62.0 ## 14 4 1 1 1 48.8 ## 15 4 0 0 1 45.5 ``` --- *Example: Classical N, P, K factorial experiment on the growth of peas conducted on 6 blocks with 4 measurements each.* ```r ggplot(npk, aes(x = block, y = yield, fill = block)) + geom_boxplot() + theme(legend.position = "none") ``` <img src="lecture2_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-20-1.png" width="800px" /> --- *Example: Classical N, P, K factorial experiment on the growth of peas conducted on 6 blocks with 4 measurements each.* ```r mod <- aov(formula = yield ~ block, data = npk) summary(mod) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## block 5 343.3 68.66 2.318 0.0861 . ## Residuals 18 533.1 29.61 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- layout:true # Two-way ANOVA --- What if you were able to group the data using more than one categorical variable? Consider data `\(\{X_{ijk}\}\)` assumed to come from `\(\text{N}(\mu_{jk},\sigma^2_{jk})\)`. - The first category runs from `\(j=1,\dots,m\)` (e.g. groups) - The second category runs from `\(k=1,\dots,h\)` (e.g. treatment) -- Data looks like this: | | Treatment 1 | Treatment 2 | Treatment 3 | |:------:|:--------:|:--------:|:--------:| | Group 1 | `\(X_{111},X_{211},X_{311}\)` | `\(X_{112},X_{212},X_{312}\)` | `\(X_{113},X_{213},X_{313}\)`| | Group 2 | `\(X_{121},X_{221},X_{321}\)` | `\(X_{122},X_{222},X_{322}\)` | `\(X_{123},X_{223},X_{323}\)`| | Group 3 | `\(X_{131},X_{231},X_{331}\)` | `\(X_{132},X_{232},X_{332}\)` | `\(X_{133},X_{233},X_{333}\)`| --- A natural question to ask is whether all `\(m \times h\)` group means `\(\mu_{jk}\)` are equal to each other `\begin{align*} H_0:& \text{ population means are all equal} \\ H_1:& \text{ population means are not equal} \end{align*}` You can calculate the test statistic by hand as well using an ANOVA table (do a Google search for this). The test statistic also has an `\(F\)` distribution. --- *Example: Classical N, P, K factorial experiment on the growth of peas conducted on 6 blocks with 4 measurements each.* ```r head(npk, n = 15) ``` ``` ## block N P K yield ## 1 1 0 1 1 49.5 ## 2 1 1 1 0 62.8 ## 3 1 0 0 0 46.8 ## 4 1 1 0 1 57.0 ## 5 2 1 0 0 59.8 ## 6 2 1 1 1 58.5 ## 7 2 0 0 1 55.5 ## 8 2 0 1 0 56.0 ## 9 3 0 1 0 62.8 ## 10 3 1 1 1 55.8 ## 11 3 1 0 0 69.5 ## 12 3 0 0 1 55.0 ## 13 4 1 0 0 62.0 ## 14 4 1 1 1 48.8 ## 15 4 0 0 1 45.5 ``` --- *Treatment: Nitrogren* <img src="lecture2_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-23-1.png" width="800px" /> --- *Treatment: Phosphate* <img src="lecture2_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-24-1.png" width="800px" /> --- *Treatment: Potassium* <img src="lecture2_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-25-1.png" width="800px" /> --- Here's the code for the plot ```r ggplot(npk, aes(y = yield, x = K, fill = block)) + geom_boxplot() + facet_grid(. ~ block) + scale_x_discrete(label = c("K=0", "K=1")) + labs(x = NULL) + theme_bw() + theme(legend.position = "none", axis.ticks.x = element_blank()) ``` --- ```r mod <- aov(formula = yield ~ block + N, data = npk) summary(mod) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## block 5 343.3 68.66 3.395 0.0262 * ## N 1 189.3 189.28 9.360 0.0071 ** ## Residuals 17 343.8 20.22 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` -- ```r mod <- aov(formula = yield ~ block + P, data = npk) summary(mod) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## block 5 343.3 68.66 2.225 0.0992 . ## P 1 8.4 8.40 0.272 0.6086 ## Residuals 17 524.7 30.86 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- ```r mod <- aov(formula = yield ~ block + K, data = npk) summary(mod) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## block 5 343.3 68.66 2.666 0.0590 . ## K 1 95.2 95.20 3.696 0.0715 . ## Residuals 17 437.9 25.76 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- layout: true # Three-way ANOVA and beyond --- Indeed, it is possible to test the grouping effect of more than two categorical variable on the data. ```r mod <- aov(formula = yield ~ block + N + P + K, data = npk) summary(mod) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## block 5 343.3 68.66 4.288 0.01272 * ## N 1 189.3 189.28 11.821 0.00366 ** ## P 1 8.4 8.40 0.525 0.47999 ## K 1 95.2 95.20 5.946 0.02767 * ## Residuals 15 240.2 16.01 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` --- Interaction effects! ```r mod <- aov(formula = yield ~ block + N * P * K, data = npk) summary(mod) ``` ``` ## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F) ## block 5 343.3 68.66 4.447 0.01594 * ## N 1 189.3 189.28 12.259 0.00437 ** ## P 1 8.4 8.40 0.544 0.47490 ## K 1 95.2 95.20 6.166 0.02880 * ## N:P 1 21.3 21.28 1.378 0.26317 ## N:K 1 33.1 33.13 2.146 0.16865 ## P:K 1 0.5 0.48 0.031 0.86275 ## Residuals 12 185.3 15.44 ## --- ## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1 ``` We'll circle back to this we look at linear models. --- layout:false class: inverse, middle, center # Summary --- ### Summary of tests | Method | Use | Assumptions | |-------------------|---------------------------------------------------------|---------------------------| | `\(t\)`-test | Test for means (one and two samples) | Data normally distributed | | Paired `\(t\)`-test | Test for means when data is pairwise | Data normally distributed | | One-way ANOVA | Test for means in different groups | Data normally distributed | | Two-way ANOVA | Test for means in different groups and treatment groups | Data normally distributed | | `\(Z\)`-test | Test for proportions | Large sample size | | `\(\chi^2\)`-test | Independence in contingency tables | Cell counts >5 | | `\(\chi^2\)`-test | Goodness of fit test | Cell counts >5 | | Fisher exact test | Independence in contingency tables | Small cell counts | --- layout: true ### Practical issues --- - What if my data is non-normal? - `\(t\)`-tests and ANOVA assumes that the data is normally distributed, so this assumption is violated. **Possibly invalid inferences!** - If sample size is large enough, this probably won't matter so much due to the CLT. - Also depends on the severity of non-normality (test it!) -- - What if I don't have a large sample size? - Alternatives are [Wilcoxon signed-rank test](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilcoxon_signed-rank_test) and [Mann-Whitney U test](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mann–Whitney_U_test) in place of `\(t\)`-tests and tests of proportions, and [Kruskal-Wallis test](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kruskal–Wallis_one-way_analysis_of_variance) and [Friedman test](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedman_test) for ANOVA (there are also available R functions for these). --- - What about heteroskedasticity? - `\(t\)`-tests and ANOVA assumes that the data come from a normal distribution with similar variances. - You could test this assumption (Levene's test). - For the `\(t\)`-test, can use Welch's test (recommended even if Levene's test fails). - For the ANOVA, nothing much we can do... -- - Any other tests I can use? - All of the tests we described are **parametric** tests. - There are several non-parametric tests that can be employed which relaxes the assumption of a particular distribution being required. - Example: [Permutation test](https://bit.ly/387s4cC), Bootstrap. --- layout: true ## Testing for non-normality --- Check histogram ```r ggplot(data.frame(precip), aes(x = precip, y = stat(density))) + geom_histogram() + geom_line(stat = "density", size = 1) ``` <img src="lecture2_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-32-1.png" width="800px" /> --- QQ-plots: Check quantiles of the data against quantiles of a normal distribution ```r ggplot(data.frame(precip), aes(sample = precip)) + stat_qq() + stat_qq_line() ``` <img src="lecture2_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-33-1.png" width="800px" /> --- layout:false class: inverse, middle, center # END <!-- --- --> <!-- *Treatment: All* --> <!-- ```{r, fig.width = 6, fig.height = 3.6, out.width = "800px", message = FALSE, warning = FALSE, echo = FALSE} --> <!-- npk$NPK <- (as.numeric(npk$N) - 1) * (as.numeric(npk$P) - 1) * (as.numeric(npk$K) - 1) --> <!-- npk$NPK <- factor(npk$NPK) --> <!-- ggplot(npk, aes(y = yield, x = NPK, fill = block)) + --> <!-- geom_boxplot() + --> <!-- facet_grid(. ~ block) + --> <!-- scale_x_discrete(label = c("NPK=0", "NPK=1")) + --> <!-- labs(x = NULL) + --> <!-- theme_bw() + --> <!-- theme(legend.position = "none", axis.ticks.x = element_blank()) --> <!-- ``` -->